Arson meets on Monday.

Assault on Tuesday.

Mischief meets on Wednesday.

And Misinformation meets on Thursday.

-Chuck Palahniuk, Fight Club

Mike Judge’s Office Space (1999) became an instant cult classic for how it tapped into the disjointed sense of belonging that Generation X felt going into the new millennium. At first glance, a white-collar office job, in theory, would have been better than the backbreaking blue-collar work that baby boomers benefited from. More productivity, more safety, more wealth, and, hey!, the fall of Communism, what could go wrong? Francis Fukuyama had proclaimed the “end of history” in favor of Liberal democracies and free market capitalism in 1992. Now we could use the power of the dollar, inflated against other currencies, to vacuum up the world’s production of goods, become gluttons for the system, and sell them, uhh, idk, “software”? What more could people want than jobs handling spreadsheet reports, privatizing software and creating chokepoints, helping to close down physical bookstores/record stores by moving everything online, being “free”?

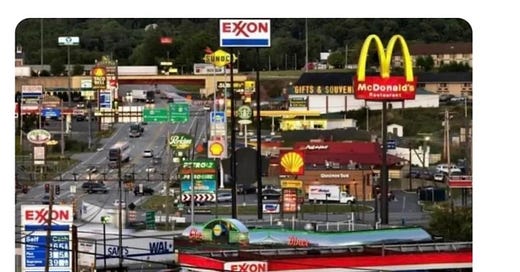

This feeling reverberated through Gen X pop culture, which included The Matrix (1999)—where a hacker, once seen as an anarchist figure, finds out there’s a darker reality beneath the surface—Kill the Man (1999), a forgotten classic about a small copy machine shop (if anyone remembers them) fighting the good fight against giant corporations like Staples (which, in turn, is now in decline)—or, in one of my personal favorites, Donnie Darko (2001), where a teenager, allegedly with schizophrenia, seems to save the world by traveling through the fourth dimension. I could lastly mention Ghostworld (2001), where two sarcastic, ironic teenage girls make fun of a world of stroads (see below), where strip-malls meet cars, semi-abandoned buildings, strip clubs, record stores, concrete, and a very conspicuous lack of canopy makes life seem meaningless. Anyone who has walked for miles in the heat, with shoddy bus stops, aggressive drivers, broken sidewalks, only to reach an anthology of chain-stores without a car might know the reasons why this type of life isn’t what anyone, absolutely fucking anyone, asked for. We could also see the definition of romance in Buffalo 66 (1998), where an ex convict kidnaps a girl to seem normal before his parents, and she eventually falls in love with him. For a happy portrayal of this period, one could turn to the bleak streets of Nashville (“Ohio”) in Gummo (1997), where, according to Wikipedia, you’ll encounter a magical journey through “drug abuse, violence, homicide, vandalism, mental illness, poverty, profanity, homophobia, sexual abuse, sexism, racism, suicide, grief, prostitution, and animal cruelty.” The director “avoided any romantic notions regarding America, including its poor and mentally disabled.” You could always define yourself “against the system,” but, as the film SLC Punk (1998) might remind you with full chagrin, sometimes you have to go with the system. In any case, all the identities and sub-cultures people found—punk, anarchism, anti-WTO, Grunge, Hip-Hop, or a grey-haired Marxism-Leninism—would be inevitably commodified into Chinese-made Che Guevara shirts. Resistance, then, might seem like pure self-violence, an attempt at finding something beyond.

It might have been a coincidence that the Columbine High School shooting took place the same year that Fightclub’s film adaptation came out. The novel was from 1996, but, I would argue, it captured something “in the air” of an exhaustion with mindless consumption. One could read all the psychiatric reports about the two shooters, then, who shocked the world before mass-shootings became as mundane as brunch, one could read all the media frenzy about how Marilyn Manson’s music was the cause of violence (and not their ability to have access to weapons of war), and we could repeat the yearly, inane babble about causality, but, given the fact that this violence became quotidian, it seems misplaced. In one of their words, “I do shit to supposedly ‘cleanse’ myself in a spiritual, moral sort of way... trying not to ridicule/make fun of people ([name omitted] at school), yet it does nothing to help my life morally.” A constant bombardment of normalized violence and gaslighting, a search for a cleansing feel eerie when one reads Fightclub.

The novel begins with an explanation of how to make a bomb. A man places a gun inside another man’s mouth in a cold-open narrative technique and the readers are thrown into a scene without context, hoping to draw them in. From the beginning of the story through the description of Project Mayhem, the tale feels like a nostalgic return to The Anarchist Cookbook (1971), which, tragically, gave incorrect directions to its users and caused a lot of incidents of misplaced culinary arts. There’s constant references to nitroglycerin, napalm, paraffin, and other substances that feel like you’re reading the back of a liquid, plastic container you use to clean your toilet.

The main character finds early on that his apartment was blown up. He catalogs all his items for the reader:

Something which was a bomb, a big bomb, had blasted my clever Njurunda coffee tables in the shape of a lime green yin and an orange yang that fit together to make a circle. Well they were splinters, now. My Haparanda sofa group with the orange slip covers, design by Erika Pekkari, it was trash, now. And I wasn’t the only slave to my nesting instinct. The people I know who used to sit in the bathroom with pornography, now they sit in the bathroom with their IKEA furniture catalogue. We all have the same Johanneshov armchair in the Strinne green stripe pattern. Mine fell fifteen stories, burning, into a fountain. We all have the same Rislampa/Har paper lamps made from wire and environmentally friendly unbleached paper. Mine are confetti. All that sitting in the bathroom. The Alle cutlery service. Stainless steel. Dishwasher safe. The Vild hall clock made of galvanized steel, oh, I had to have that. The Klipsk shelving unit, oh, yeah. Hemlig hat boxes. Yes. The street outside my high-rise was sparkling and scattered with all this. The Mommala quilt-cover set. Design by Tomas Harila and available in the following:

Orchid.

Fuschia.

Cobalt.

Ebony.

Jet.

Eggshell or heather.

It took my whole life to buy this stuff.

Thus begins the main character’s quest to freedom. An explosion frees him from his possessions. I won’t say who Tyler is, in case you don’t know the story, but, simply speaking, he leads the character to a new life:

Tyler says I’m nowhere near hitting the bottom, yet. And if I don’t fall all the way, I can’t be saved. Jesus did it with his crucifixion thing. I shouldn’t just abandon money and property and knowledge. This isn’t just a weekend retreat. I should run from self-improvement, and I should be running toward disaster. I can’t just play it safe anymore. This isn’t a seminar. “If you lose your nerve before you hit the bottom,” Tyler says, “you’ll never really succeed.” Only after disaster can we be resurrected. “It’s only after you’ve lost everything,” Tyler says, “that you’re free to do anything.”

In the Gospel of Tyler Durden, you can’t simply abandon desires, or let go of things, meditate them away, pray for wisdom, give to the poor. No, for Tyler Durden, you have to destroy them. The question of violence guides the whole story to give it a shot of adrenaline, Tyler guides the haphazard, bored, depressed, Xanax-filled crowd of society and gives them a few simple rules along with a place where they can gather and beat the shit out of each other. There is something about a generation of men (because they are, all, absolutely intermittent testosterone bags with failing livers) who never went to war, don’t find ideology promising, can’t see themselves fit into society, feel emasculated, meaningless beating the absolute shit out of each other. Violence creates redemption?

In fact, it may not be violence per se but the rush to nothingness that makes the process violent. Praying, meditation, reading philosophy takes time, and none of this motley crew seems to have any of it. They’re exhausted by awful jobs, lonely apartments, and want answers now. As I wrote in my previous blog post about ways, paths, methods, I return to this question but in the form of accelerationism. As I mentioned then, whether in Buddhism—Sunyata—Christian mysticism—Kenosis—or, even, dialectics—both Plato’s Parmenides and Hegel’s Logic create an equivalence between being and nothingness, let alone Sartre and others—the search for nothingness is something overlooked in a society that promises abundance, pleasure, hedonism, consumption (gluttony?), and needs this as a basis of its reproduction. The U.S. deficit, counter to popular belief, is a function of sustaining a consumer economy, so that surplus economies (like China) have buyers. Perhaps, then, in a busy 9-5 (in the 90s it was already a myth with overtime), the search for kenosis came through rapid violence.

In one of two or three scenes where characters are forced to decide who they are, violence and adrenaline are used to reach the conclusion. Thus spoke the novel:

“The mechanic yells out the window, “As long as you’re at fight club, you’re not how much money you’ve got in the bank. You’re not your job. You’re not your family, and you’re not who you tell yourself.” The mechanic yells into the wind, “You’re not your name.” A space monkey in the back seat picks it up: “You’re not your problems.” The mechanic yells, “You’re not your problems.” A space monkey shouts, “You’re not your age.” The mechanic yells, “You’re not your age.” Here, the mechanic swerves us into the oncoming lane, filling the car with headlights through the windshield, cool as ducking jabs. One car and then another comes at us head-on screaming its horn and the mechanic swerves just enough to miss each one. Headlights come at us, bigger and bigger, horns screaming, and the mechanic cranes forward into the glare and noise and screams, “You’re not your hopes.”

The point of the exercise, here, is the following question:

““What,” he says, “what will you wish you’d done before you died?” With the oncoming car screaming its horn and the mechanic so cool he even looks away to look at me beside him in the front seat, and he says, “Ten seconds to impact. “Nine. “In eight. “Seven. “In six.” My job, I say. I wish I’d quit my job. The scream goes by as the car swerves and the mechanic doesn’t swerve to hit it.

The path to enlightenment is not through the holy book, the Tao, political redemption, or other traditional, time-consuming enterprises, but through an addictive approach to death. Instead of waiting for enlightenment, death can be pursued, sometimes in a therapeutic way. Raymond K. Hessel, threatened with imminent death at the hands of Tyler Durden’s creed, finds his dream career. At the end of a gun, Tyler forces Raymond to confess his dream career. He takes his I.D., tells him he will check up on him, and, if he does not become a Vet as he once wished, he would kill him. After sobbing, thinking he would die, Raymond is reborn, baptized through fear, with Tyler instilling the Holy Spirit in him, saying: “Raymond K. K. Hessel, your dinner is going to taste better than any meal you’ve ever eaten, and tomorrow will be the most beautiful day of your entire life.” Only through the face of nothingness does life find meaning, purpose, and direction. Heidegger, after all, wanted to get rid of they-time, to have us live every day as if death and birth existed in every Moment, making every decision authentic, meaningful, and true.

Perhaps violence creates meaning, like it arguably did for early 20th-century fascism, or admirers of Ernst Jünger’s tales in the trenches. As fucking stupid as this novel is, it spoke then to something which would only balloon in the 21st century, where, not satisfied with shootings in kindergartens, elementary schools, homes, or anywhere else, we normalized a pandemic and a genocide to maintain our sense of normalcy. Also sprach Tyler Durden:

““Remember this,” Tyler said. “The people you’re trying to step on, we’re everyone you depend on. We’re the people who do your laundry and cook your food and serve your dinner. We make your bed. We guard you while you’re asleep. We drive the ambulances. We direct your call. We are cooks and taxi drivers and we know everything about you. We process your insurance claims and credit card charges. We control every part of your life. “We are the middle children of history, raised by television to believe that someday we’ll be millionaires and movie stars and rock stars, but we won’t. And we’re just learning this fact,” Tyler said. “So don’t fuck with us.”

If you fucked with them, Tyler might piss in your soup.